What is it that distinguishes man from non-man? This question suggests one of two possible contrasts, depending on how you interpret ‘man’. It could refer to ‘man’ as in ‘mankind’. Man as opposed to beast. Or to ‘man’ as in ‘male’. Man as opposed to woman. In this blog and my next I intend to explore both contrasts. First, ‘Man Vs Beast: what is it that separates us from the animals?’ In the next, ‘Man Vs Woman: are men and women interchangeable?’.

These are important questions for our time. We live in a society that has become very confused about human identity. Some have blurred the lines so much between man and beast, that to eat meat is considered murder. Some are so despondent with our negative impact on the earth that they genuinely believe it better to not have children, or for humanity to not exist at all, for the sake of the earth. As the possibility looms of AI replacing much of the workforce, and emulating human consciousness and thought, there are questions raised about what makes someone truly human. Widespread belief in evolutionary biology, from people who aren't really trained scientists, has resulted in an incredibly reductionist view of humanity, boiling everything that makes us unique down to chance and a more developed brain. Unless we understand what makes us us, we can never understand our identity and purpose.

First, some caveats. Despite the similarity of the titles, I am not intending by comparison to suggest that man's relationship with the animals is equivalent to man's relationship with women. The point of the similarity between the two titles is merely that I find the wordplay pleasing, and that both blogs are looking at aspects of manhood: humanity first, maleness second.

Nor am I wanting to start a debate about whether the use of ‘man’ to mean ‘human’ is sexist or outdated. It is certainly a well worn usage of the word, and one that has a lot of history behind it. It is also controversial for some modern audiences, and one can understand why. For now, since I want my writing to be crystal clear, and the two different blogs will be regularly talking about both humanity and males, I will endeavour to use terms like ‘mankind’ and ‘humanity’ rather than ‘men’ when what I mean is men and women, to avoid both offense and confusion (the only exception being when ‘man’ just feels better literarily).

With caveats out the way, let's begin: what is it that separates us from the animals? What is at the heart of the difference between mankind and the rest of the living creatures?

Man as Animal

Some in today's society would argue, ‘Very little’. We too, technically, are as much ‘animal’ as any rat or worm or whale. This is the cry of the secularist, the evolutionary biologist, the atheist, the materialist, the naturalist, the vegan. We were fortunate to develop bigger brains. That is about as far as the difference goes. To say anything more is species-ist.

Now you may be expecting me to rip into this worldview right away. If so, you will find that expectation subverted, for I am nothing if not nuanced. Instead, I want to start by noting that this view has a lot to commend it. First, it is mostly true on the level of cells, physiology, genetics, and other biological fields. Stare into a dog’s eyes, and eyes very much like your own will stare back. Dissect a pig's heart, and you will see something very similar to the one currently pumping blood around your body. Watch sheep have sex or give birth (not that I'd encourage this sort of bestial voyeurism), and you'll find it alarmingly similar to our own process of procreation. And if anyone looks at a monkey and says they don't look or act even remotely similar to us as human beings, I'd heavily question their skills of observation. The bottom line is that at every level, from our blood to our brain, our spine to our spleen, our nervous system to our nostrils, we have an awful lot in common with an awful lot of the animal kingdom, and most especially our fellow mammals.

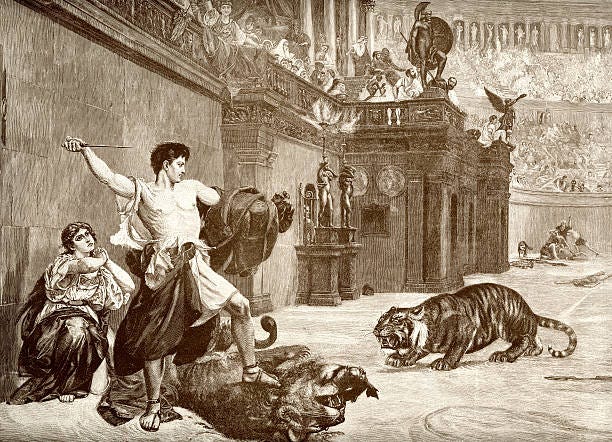

Further, our day-to-day activity is very much ‘animalistic’. Watch any nature documentary and you ought soon be struck by the realisation that animals adapt for two basic activities: war and romance. War is about food and survival, hunting or being hunted, avoiding death and finding the nutrition needed for life. Romance is about finding a mate, to produce offspring, to give the next generation the chance to do the same. Whether it's the peacock's feathers or the tiger’s stripes, the turtle's shell or the lion's teeth, it's all for the same basic things: food, self defence, hunting, securing a mate, reproduction. Now watch the history channel, and you'll see much the same. Sex and violence, food and reproduction, survival and the next generation. War and romance. Us humans are stuck in the same rat race, the same circle of life, as the other creatures under the sun. Our life consists of the same basic daily endeavours.

And beyond scientific and observational evidence, the Bible makes a clear case for this equality among species. Whilst human beings stand apart from the rest of creation (and we will come to that later), they are still made on the same day as the other living creatures on the earth. Yes, God animates us with the breath of life1. But that same breath animates all flesh.2 Psalm 8, perhaps one of the go-to proof texts for humanity’s difference to and superiority over the beasts, ironically only makes sense if the starting assumption, the default, is that mankind is equal to and of a kind with the rest of creation. Hence the shock of the question: ‘...what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?’. The amazing thing about all that follows, about man's placement above the rest of the creatures, is precisely that we did not deserve or have a right to this special dignity. Who are we, that God would consider us so highly? Us creatures of dust, like the rest? What did we do to be crowned with such glory and honour?

Perhaps most morbidly of all, the author of Ecclesiastes notes that, in death, all God's creatures are created equal:

I said in my heart with regard to the children of man that God is testing them that they may see that they themselves are but beasts. For what happens to the children of man and what happens to the beasts is the same; as one dies, so dies the other. They all have the same breath, and man has no advantage over the beasts, for all is vanity. All go to one place. All are from the dust, and to dust all return. Who knows whether the spirit of man goes upward and the spirit of the beast goes down into the earth?3

This is probably the clearest proof-text of the lot. God, by cursing us with death, wants us to see that we ourselves are but beasts. We suffer the same fate. We too return to dust. A rotting corpse looks and smells much the same, whether it's a man or a mouse. We are not ‘built different’. We are flesh and blood, guts and gore, ashes and dust. This passage also explains why it's important for us humans to realise this. We want to be humble, not entitled. We want to recognise that we cannot escape the same cycles of life, the same created order, that the lesser creatures submit to. We want to acknowledge our creatureliness, our physicality, our need to eat, sleep, and mate. We have the same breath and the same destiny in this life. As animals, we ought to be humble.

Further, this perspective helps us avoid the danger of over-spiritualising life on earth (or, perhaps better, the danger of under-spiritualising the physical aspects of life on earth). It would be easy to think that, as conscious beings, we have transcended the material realm. That life now for the (Christian) human is all about thinking, meditating, praying, ruminating, Bible studies, ideas, the Spirit, heaven, and so on. The alternative isn't to shun these, but to integrate them into the understanding that life now is also about birth, food, drink, work, marriage, sex, offspring, and so on. That we're mind and matter. Breath and dust. Body and soul. Flesh and spirit, indeed an enfleshed spirit. That we exist as a single whole that integrates both aspects. And so the physical aspects of life are as much part of who we are, and of the created order, and of what it means to be human, as the ‘spiritual’ aspects are. In fact, if spiritual is shorthand for ‘Christian’ or ‘important to God’, then these activities are just as ‘spiritual’ as any bible study or prayer meeting.

But I somewhat digress. To get back to the point, we are animals. We are part of the same category of being as the beasts of the field and the birds of the air. We are creatures, made by God. We exist within the same ecosystems, and take part in the same struggle for survival, as every other species.

More Than Beasts

But we are more than just animals. And this is where the secularist, the evolutionary biologist, the atheist, the materialist, the naturalist and the vegan can, if they're not careful, go too far. Because just as I'd question the observation skills of anyone who says we look nothing like monkeys, I'd also question the observation skills of anyone who thinks that we're fundamentally the same, or that there's no significant difference between us and the rest of the animal kingdom.

After all, when was the last time you saw an animal communicate with language, either spoken or written, on a level of complexity akin to human languages? When was the last time you saw an animal ride a vehicle that it had designed, engineered and built? When was the last time an animal deliberately fasted for days, despite food being readily available? When was the last time an animal kept humans in a zoo, or used human skin for clothing? When was the last time an animal wrote a blog about the difference between them and mankind?

We could explain away these differences as being merely evolutionary good fortune. All down to our better brains, which developed purely to help us survive. To say that such an explanation is unsatisfying is an understatement. The Bible says something much more significant. We are different because God made us different. God made us in his image.4 This means that we are, on an ontological level, distinct from any other creature. There is something unique to us that makes us the way we are. That explains our seemingly higher position within the world’s ecosystems. Our seemingly very different way of interacting and forming relationships (both with each other and with other animals). Our sense that our consciousness, thoughts, emotions, passions, ambitions, desires and volitions are not the same as what other species experience.

Being in God's image means at least three things. It means we reflect God's nature as those who are in some way like God. It means that we relate to God, as creatures made to be able to commune with him. And it means that we rule under God, over the rest of creation. This is all either explicit or implicit in Genesis 1-2. God gives us dominion over the other creatures. God talks to us and gives us commands, in a way that he doesn't with the other creatures. We are the pinnacle of creation, God's last act before he rests.

In practical terms, this means that the differences between us and the animals are endless. So I simply want to focus on two, which I think get at the heart of the distinction. First, that man rules over the animals. Second, that man rules over himself.

Humanity’s Rule Over Creation

That man rules over the other animals is explicit in Psalm 8 and Genesis 1, both passages mentioned already. I claimed that our rule over the rest of creation, and the fact that we reflect something of God to creation and each other, are two key aspects of humanity's image bearing nature. But in some sense the former is merely an extension of the latter. God is the God who rules the cosmos, who spoke creation into being and brought light into darkness, form into void, order into chaos, life into death. His command for us to fill the earth with life and to have dominion over it is a continuation, extension and appropriation of his work in creation. Our rule is a reflection of his rule. It is one of the ways in which we are like God. Of course we do so in a different way. We do not create, we procreate. Our efforts do not bring anything out of nothing, nor can we bring life out of death. Rather, we work with and fulfill the latent potential with which God made the cosmos, and use our God-given life to beget further life. And yet - despite the difference - in so doing we reflect something of God's great nature, and are graciously allowed to participate in his great mission, to fill the earth with his glory.

This has huge implications for sex, marriage, academia and work. Humanity can partake in and be a means of God’s providential care for his creation, and can create ordered and well-run civilisations from disorder and chaos. It is no surprise then that Paul borrows an image from contemporaneous (to him) political philosophy, of the well-run state as a human body, as his way of describing the church. In the great human project, the church ought to be the forerunner, the pinnacle of good leadership, functional teams, orderly conduct, relational harmony, and so on. The epitome of ordered human living. And just as the church ought now be a bastion of such good rule, so wider human culture and civilization ought to be ever growing in knowledge, sophistication, justice, mercy, order, lawfulness, and more. Of course many empires and nations have failed in this. This is our ultimate, eschatological hope, as pictured in Daniel 7. Following several beastly kingdoms, at last comes one like a son of man, a truly human kingdom ruled over by a human king. But it is a hope that, at the very least in the church, has been inaugurated by the Lord Jesus, and that we ought to aspire to today.

Humanity is to rule over the creatures. But as an aside, we must integrate this with our first claim, that we too are animals. Just as the king of Israel was not to be an outsider, but a brother and an equal, an Israelite first and king second, so too we rule over the creatures as fellow creatures. We rule not as gods over creation, but as stewards within creation, ourselves a part of the creation order and subject to it. The earth is ours by gift, not right. The earth, and all that is in it, belongs to the Lord.

This should shape the way that we rule. As mentioned before, we should have great humility before God, and gratitude and wonder like David in Psalm 8, that God should bestow such honour upon us. It must certainly mean that we care for the other creatures. As much as ‘creation care’ and ‘stewardship’ have become woke catchphrases for progressive ‘Christians’, the conservative is also in real danger of completely ignoring the numerous and unambiguous signs throughout scripture that God cares about plants and animals. Of course some take this too far. We don't just rule over the beasts, we also war with the beasts. We live now in a cursed world, tainted by violence. And so eating animals for food is entirely appropriate and morally acceptable in a world where animals also eat us,5 though no one should take offence at someone choosing a vegan diet for personal, medical or environmental reasons. We ought not be too squeamish about the violence present in the animal kingdom. Trees and oil and metal are there for us to use to build, engineer and manufacture. But we need to use these resources responsibly, fairly, and sustainability. Our rule ought to be good, not bad, for the rest of creation.

I have seen several Facebook posts asking the question ‘If you could remove one thing from Earth, what would it be?’ and many of the top comments answering ‘Humans’. This is absolutely unfathomable to me, that one could be so against their own species. And it is a real shame that anyone would think this since, at least in theory, God created humanity to be good for the world. The land needed working before Adam turned up.6 All creation looks forward to the revealing of the sons of God.7

Humanity’s Rule Over Self

And part of why we're able to rule the animals is that humanity - at its best - is also capable of extraordinary self-rule. Our ability to delay gratification and look to a future beyond the immediate present is what makes political society possible. So try putting a huge pile of meat in front of a hungry lion, and see how long it holds itself back for. Or try asking a stag in rutting season to control its sexual urges, and see what its ability for abstinence is like. In the animal world, lusts are either instantly gratified, or involuntarily left unfulfilled. Animals do not fast. Animals are not voluntarily celibate. In this, the Roman Catholic priest and the Muslim share a common humanity, and one that is perhaps neglected by many low-church evangelicals. The ability to say no to the animalistic basics. To resist the bestial impulse, and to wait or abstain. Of course, we still need to eat at some point. To completely abstain from all animal urges, all the time, would also be subhuman, since humans are animals, as has been shown. We mustn't fight God's created order. But we ought to be lord over our own wants and desires, not the other way round.

One might question whether such self-rule really separates us from the lesser creatures. Surely, if one thought hard enough, they might find instances of great self control in the animal world too? I found a few such counter examples, but I think they truly are exceptions that prove the rule. So one might imagine the hungry lioness that allows itself to go without food so that its children can eat, an image seen in many a nature documentary, as the dutiful parent sits back as its cubs get first pick of the carcass. Whilst in many ways this is quite a remarkable act of generosity when coming from a lion, it isn’t the same for two reasons. The first is that fasting when there's plenty of food available is very different to going hungry when there's not enough for everyone. The lioness would not be abstaining if there were an unlimited antelope buffet on offer. The second is that, in this act of charity, the lioness is simply submitting to a higher animal instinct: the preservation of her young for the success of the next generation.

Or consider the well-trained dog, who can sit obediently without snatching at the snack in front of it. But surely this example serves only to accentuate the point? Nothing could be further from self-rule than the obedient lapdog that's been conditioned by its human master. And again, such conditioning relies on animal instincts. The dog waits, because it knows the treat will come in the end.

So self-rule is, I suggest, a distinctly human characteristic. Which is why it's all the more terrible when we fail to control our urges. The biblical authors often describe sin in very animalistic and bestial terms. The Israelites who worship their golden calf end up cow-like themselves: stiff-necked, out of control, let loose to the derision of their enemies.8 The fool is like a dog returning to its vomit,9 not only unable to control its urge to eat, but unable to see how disgusting its current meal of choice really is. False teachers are described vividly by Peter in his second Epistle:

But these, like irrational animals, creatures of instinct, born to be caught and destroyed, blaspheming about matters of which they are ignorant, will also be destroyed in their destruction, suffering wrong as the wage for their wrongdoing. They count it pleasure to revel in the daytime. They are blots and blemishes, reveling in their deceptions, while they feast with you. They have eyes full of adultery, insatiable for sin. They entice unsteady souls. They have hearts trained in greed. Accursed children!10

They are characterised as irrational animals and creatures of instinct. What follows is an appalling description of licentiousness and sensuality. They run only on instinct, doing whatever feels good in the moment, imagining themselves free to engage in whatever activity they please. Daytime revelry, feasting, lustful eyes, greedy hearts. This is what animalistic humanity looks like at its worst.

To be clear, eating food and having sex are not sinful activities, if done rightly. And Paul discourages any long periods of abstinence between married couples,11 and encourages us to eat and drink and marry12 (an encouragement I have very much taken to heart as I await my own wedding in two months!). So the solution here is not asceticism or permanent abstinence. But part of what distinguishes us from other creatures is that we ought to be able to rule over our animal instincts, and not be ruled by them. For a husband or wife to want sex is perfectly natural. Regular sex for a married couple is important and right. For a husband to be unable to go without sex, and to need his horny urges gratified instantly at any given moment, is subhuman. And those same good and human instincts to have sex, reproduce and survive are, when allowed to go forth unrestrained and uncontrolled, often the origin of greed, gluttony, lust, adultery, rape, murder, fornication, pornography, and all sorts of other evils.

This raises a question about how these desires can be both human and subhuman. How the same desires to have sex and to survive can be both part of God's good created order, and the beginnings of sin. But for the theologically minded Christian, there is no tension here. This is simply the doctrine of total depravity, and of evil. It is often claimed that evil has no existence in itself, but exists only as a corruption and perversion of the good. And every good human desire has, as a result of the fall, been affected and tainted with sin. It should be no surprise that sin targets those things that come most naturally to us as creatures, and should encourage us to indulge in them beyond the boundaries of God's law. Ultimately, true self control is a fruit of the Spirit. Only with a renewed mind can we fully start to order our desires rightly, and live fully human lives.

Conclusion

There is much more that could be said on this question. For now I’ll conclude with why this question, and my answers, are important. We do live in a world that’s very confused about what it means to be human. All jokes aside, I have nothing against vegans, especially Christian ones. But there is a genuine danger of over-identifying ourselves with the rest of animal-kind, as if we are simply ‘top animal’, without properly considering our unique position as those made in the image of God. Such wrong thinking is tragically reductionistic about human nature, and fails to look with open eyes at the many and obvious differences staring us in the face every time we look at the civilisations we have built, or even just into another's eyes.

There is perhaps a lesser danger too of overlooking my first point. Of over spiritualising life now, or under spiritualising the physical aspects of life now. Acting as if we are beyond sex and survival. In the modern evangelical church, this sort of theology of ‘let’s just look forward to the new creation and not worry about food and drink and sex now’ ironically often seems to come from those for whom survival has never really been a question, and who have ready access to food and water from years of human work, engineering and societal progress. And it is explicitly false teaching in the New Testament.13

So there is a difference between us and the rest of the animals. It is vital for us to have a biblical anthropology if we are to truly understand our identity and place in the cosmos. We are made in God's image, to reflect his glory, relate to him as children, and rule under him.

So take part in the great human project to have dominion. Work, or marry and fill the earth with life, or study God's universe, or think about how you can make it better, do good, promote flourishing. Not everyone needs to do all these things, and there may be many good reasons to stay single. But every human ought somehow, if they're able, to contribute to our dominion over creation.

And have self control. Do not be like the animals. God has made you greater than them, so do not resort to following your base desires like a creature of instinct. Wait. Fast. Abstain. Deny. Not all the time, and not in every way. But when necessary and when helpful. Do not let your animalistic desires run your life for you. Do not let them distract you from your mission, whatever mission God may have given you. Do not let them give birth to sin. Be a (hu)man.

Genesis 2:7

Genesis 7:15

Ecclesiastes 3:17-21

Genesis 1:26-27

Genesis 9:1-7

Genesis 2:5

Romans 8:19

Exodus 32:25

Proverbs 26:11

2 Peter 2:12-14

1 Corinthians 7:5

1 Timothy 4:1-5, 5;14

1 Timothy 4:1-5

Wonderfully helpful. Might I add another point? It was common in seventeenth-century theological anthropology to refer to man as animal religiosum: the thinking being that what most truly separates us from (other) animals is that we desire to, and need to, worship God. Man alone thirsts for the face of God. And that ties in nicely with your second point, about self rule: the ultimate example of which is forsaking this life in order to dwell with God in the next. Worship motivates dominion over our own desires (nicely indicated by the passage you refer to in 1 Corinthians 7, too).

Love the conclusion about how we should put material things and/or earthly activities in their proper place. Thank You for pulling together so many views that often appeared to be contradictory :)